A history of Alhama de Murcia

The connection with water runs from the Roman baths to the Tajo-Segura supply canal

These days Alhama de Murcia is a prosperous medium-sized town in the south-west of the Region of Murcia, approximately half way between the cities of Murcia and Lorca, and almost the only reminder of the troubled and at times desperately hard road which led to the stability enjoyed in modern times is the remains of the castle on the promontory behind the town centre.

The area proved attractive first to prehistoric settlers and then, due to the existence of the thermal springs after which Alhama was named and of mineral deposits, to the Romans, the Visigoths and the Moors. But the Middle Ages in Alhama were marked by its location as a frontier town close to the border with the Moorish kingdom of Granada, following the partial Reconquest of southern Spain by Christian forces in the 13th century. Further hardship followed under the sometimes despotic governorship of the Fajardo family, later the Marqueses de los Vélez, and it was not until the availability of water for irrigation in the second half of the 20th century that agriculture truly began to flourish.

The existence of such a large community in Alhama is thus a relatively new phenomenon, and only now is the town’s privileged location on the fertile plain of the Guadalentín valley and at the foot of the Sierra Espuña attracting residents who in the past might have chosen safer, more prosperous places in which to live.

Prehistoric man in Alhama de Murcia

Evidence of human activity in Alhama de Murcia dates back to around 3000 BC, in the Neolithic, when hot thermal springs, abundant water, the availability of shelter, the natural corridor of the Guadalentín valley and the resources of the surrounding landscape made the area an ideal location for settlements.

There is no evidence of human habitation during most of the Paleolithic, although it is thought probable that the rocky outcrops and caves of Sierra Espuña and Sierra de Carrascoy could have been inhabited, but by the end of the 4th millennium BC there were hunter-gatherer communities both on higher ground, such as Cabezo Salaoso and the castle hill, and on the plain on the left bank of the River Guadalentín in Las Ramblillas. At these sites the evidence of their presence which has come to light includes fragments of handmade ceramics with small handles which point to the existence of an agricultural community, similar to those which have been discovered in Totana and Lorca.

Cueva Luenga and El Alto de Los Zancarrones are two more of the sites which are known to date from the same period, and they have much in common with other settlements in the Region of Murcia, particularly those which were inhabited during the eneolithic (or Copper Age). This point in mankind’s development marked a transition from the use of stone tools to experimentation with the smelting of metals, although there was not yet a full understanding of how to fuse copper and tin to make the metal which would revolutionize early Man’s way of life: bronze.

The Bronze Age which followed (approximately 1800 to 750 BC) left at least two known settlements in Alhama; one on the hill of Cabezo del Murtal and another on the right-hand margin of the Rambla of Algecira. At this point burial rights had evolved - the deceased were now laid to rest in individual graves, often beneath the floor of the family home - and apart from the sites mentioned above there were others in Cabezo de los Moros, La Pita, Cabezo del Azaraque and the town centre of Alhama. Among the items recovered are two bronze arrowheads, stone milling tools and a flint sickle blade, which indicate that cereal farming was important at the time.

The end of the Bronze Age coincides with the emergence of the Iberian culture in the Peninsula, characterized by their language, ways of life, tribal society and trading activity, and although no complete Iberian site has been identified within the municipality of Alhama it is significant that in the Plaza Vieja a series of four graves was found. If this was the site of a necropolis it can be deduced that a settlement was close at hand, almost certainly on the castle hill.

Important Iberian artefacts have also been recovered, including one “kalathos” (a pottery basket in the shape of an upside-down top hat) which is now held by the National Archaeology Museum and another, unearthed in 1989, which seems to confirm that there was an important Iberian settlement on the castle hill between the 6th and 3rd centuries BC.

As trading routes grew between the Guadalentín valley and the Mediterranean coast more and more Greek-style pottery appeared, and again various discoveries along these lines have been made in Alhama (on the castle hill, in the town centre and at La Pita, Cabezo del Murtal and El Puntal). Iberian ceramics have even been found next to the Roman baths, raising the possibility that the thermal water was appreciated as long as 2,400 years ago and not discovered, as has generally been accepted, by the Romans.

The Romans in Alhama de Murcia

In the 1st century AD Alhama became an important town under the Romans, who were attracted to the area by the abundance of deposits of iron, copper and lead, and by the thermal springs.

Mines from the Roman era (the Romans took Cartagena by force in 209 BC and extended their dominance throughout what is now the Region of Murcia over the following 5 centuries or more) have been found throughout the mountains of Sierra Espuña, Sierra de Carrascoy and Cabezo Salaoso, and to exploit the warm water the Romans built a large thermal spa complex in the 1st century AD. This included areas designated for medicinal and recreational use, both of which had separate spaces for each sex, and in the medicinal area there are domed rooms with overhead openings which would have been used to regulate the temperature inside.

In the recreational area we can still see the typical layout of baths in Roman times, with the cool room ("frigidarium"), the warm room ("tepidarium") and the hot room ("caldarium"). The ovens for the hot room ("praefurnium") have also survived.

Dirty water was then expelled from the baths into tanks which were channelled out of the baths to be used for irrigation, providing an early example of the "recycling" of water which is now so common in the crop fields of the Guadalentín valley!.

All of these archaeological remains can be seen in the Museo Arqueológico "Los Baños", next to the church of San Lázaro.

As well as the baths, the Romans also left significant traces of their presence at the Roman villa sites which lie within the municipality of Alhama, including those in the villages and outlying districts of La Costera (Villa El Ral and La Casa de las Viñas), Las Cañadas (Casas de Guirao), Casa del Malo, Venta Aledo and El Puntal. They effectively colonized almost the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, introducing their agricultural model, coinage and way of life, and despite the scant evidence gathered this obviously extended also to Alhama.

Abundant archaeological evidence has been found at the villas (which were agricultural enterprises), and all of them are located at around 200 metres above sea level - presumably to avoid the flooding which can occur in the valley - along the left bank of the Guadalentín, indicating that this was the main communications route.

But eventually, as the Roman Empire declined, these prosperous villas were abandoned and the population retreated from the countryside to the safety of a walled city, reducing agriculture to a subsistence level.

The Moors in Alhama de Murcia

By the 4th century the influence of the Romans was on the wane, and Murcia was overrun by a series of invaders including the Visigoths. This state of affairs continued until the early 8th century, when Moorish forces swept across southern Spain, and in 713 the Pact of Tudmir conceded control of the area to the north Africans.

Although initially control was theoretically left to a Visigoth "governor", by the 9th century the Moors were well established in the area, and mention of the hot waters of Alhama appear in several texts. In fact, the name of the town as we know it is derived from the Arabic “Al-hamma” (thermal bath), although previously, in the year 896, Ibn Hayyan wrote about the location of “Ayn Saytan” (or “the devil's fountain”, as he called it) between Aledo and Murcia.

More references appear in the 11th and 12th century, by which time the town is referred to as “Hisn al-hamma” (the castle of the baths).

The Moors appreciated the town's strategically important location in the defence of the fertile land of the Guadalentín valley, and constructed an early fortified settlement on top of the hill where the castle now stands. At the same time they adapted the thermal baths and used other existing Roman installations, modifying them around their own traditions.

Thus, for example, the medicinal area of the baths now acquired a religious significance, and the domed roofs were adapted to allow better temperature control.

Alongside the women’s baths archaeologists have discovered tombs belonging to the Islamic burial ground or "maqbara" from the 12th century, when the town was known as Hāmma Bilaquār.

The castle, meanwhile, was one of many of strategic importance between Lorca and Murcia, and the grographer al-Idrīsī wrote in the 11th century that travellers from Murcia to Almería should pass through Qanţarat Aškāba (Alcantarilla), Hişn Librāla (the castle of Librilla), Hişn al-Hāmma (the castle of the thermal baths, or Alhama) and Lūrqa (Lorca). At the same time the Roman agricultural “villas” were now supplanted by Moorish “alquerías” such as those of Cabezo de los Moros, La Pita, La Torre de Inchola, el Cabezo de Salaoso and Azaraque almost completes the picture of Islamic Alhama.

However, it is not clear where the mosque of Alhama was located, as there is no reference in either historical or archaeological documentation.

Medieval history in Alhama

In 1243 control of what is now the Region of Murcia was ceded by the Treaty of Alcaraz to the Christian forces headed by Prince Alfonso, who would later become King Alfonso X "El Sabio” (the Wise) of Castilla. With the Reconquista of south-eastern Spain from the Moors complete, he entrusted the castle of Alhama and the land around it to one of his knights, Rodrigo de Villamayor, although at the same time Alfonso also ensured that the ultimate owner of the land was the monarchy.

Murcia was back in Christian hands but many Muslims remained in the area, becoming known as “Mudéjars”. Their situation was far from clear or secure, as the west of Murcia was now effectively “frontier territory” on the border of the Moorish kingdom of Granada, and in 1266 the Mudéjars staged a revolt against the Christian forces.

King Jaime I “El Conquistador” of Aragón, the father-in-law of Alfonso X, arrived to crush the uprising, and during the conflict one of the most important battles took place in Alhama, where the Christian troops repelled Moors who were marching to attack the city of Murcia.

Thereafter, apart from a brief interlude under the rule of Jaime’s son, Jaime II, between 1298 and 1304, Alhama remained under the control of the Crown of Castilla. This interlude followed a 2-year siege of the castle which had begun in June 1296 and ended on 3rd February 1298, when Jaime II informed his ally Muhamad II of Granada that the fortress had been successfully seized.

Just six years later, though, the signing of the treaty of Torrellas returned Alhama to the Crown of Castilla, but although a general pardon was issued by Fernando IV of Castilla to those who had supported Jaime, it was difficult to establish any kind of prosperity within the period of relative stability which followed due to the proximity of the border with Granada and the constant threat this entailed, and the post-Reconquista de-population of the area continued. In this context the ways of life which had evolved in the area over 400 years of Moorish rule persisted to a certain degree, as did their contributions to agriculture, town planning and water distribution.

From 1311 to 1326 the town belonged to the Diocese of Cartagena and was then under the control of the Infante Don Juan Manuel, Duke of Villena, before reverting to direct rule from Castilla in 1338. At this point King Alfonso XI ordered repairs at various castles, including those of Lorca, Alcalá, Bullas, Caravaca and Alhama, and in Alhama these repairs can still be seen today, as can the carved decorations on walls which were rebuilt.

In 1387 Juan I awarded the town to Alonso Yáñez Fajardo in recognition of his services in the wars against Portugal and in Granada, and the marriage of Luisa Fajardo and Juan Chacón brought together two dynastic houses, consolidating their lands and their power. In medieval times the general populace of Alhama were subjected to the whims of their governors and the demands made of them to maintain the dynastic power and prestige, and in the 15th century the Fajardo family consolidated this power by extending and rebuilding the castle which dominated the hilltop above the town.

Alonso Yáñez Fajardo extended his power in the Region of Murcia when he acquired the villas of Librilla and Molina, and the family later took control in Mula and other areas. However, the new lord was unable to protect his land from further destructive raids from the neighbouring kingdom of Granada, and crops and livestock were decimated in such incidents in 1392, 1395 and 1406.

By this stage, the population of Alhama was almost entirely Christian, and if Moorish raids made life difficult for them the situation was exacerbated by the power struggle between the Fajardo and Manuel families. The Manuels held control over the city of Murcia and launched continual attacks on rural areas nearby, and until this dispute was concluded late in the 14th century the climate of violence and fear was never far away.

Among the scant population there were still some of Moorish descent, but after the Moors were definitively expelled from Granada and the rest of Spain by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492 very few of them remained in the town. During the period the first Christian church, probably dedicated to San Lázaro, was built on what could have been the site of the Moors’ mosque, and under the current building the remains have been found of a Christian cemetery.

To give an idea of the extent of the de-population, though, traveller Hieronymus Münzer (1437-1508) reports that in 1494 Alhama consisted of “some 30 houses with a castle above on a mountain, a thermal spring with clear water and a good glass factory”.

The Fajardos consolidate their power

When the threat of Moorish incursions finally receded following the events of 1492, the community of Alhama became a more disperse and scattered one. Small settlements existed throughout the area, linked by watchtowers which attempted to warn of any danger, in locations such as Ínchola, La Pita, El Azaraque, Ascoy, Torre del Lomo and Torre de la Mezquita.

After the expulsion of the Moors the need for the castle gradually receded, and over the following century it fell out of use. But no period of prosperity followed, and after infighting among members of the Fajardo family and the conflict with the Manuels the overlords appear to have still had little interest in anything other than maximizing their own personal revenue and taking control of the strategically located castle.

If life was grim in the 15th century in Alhama, as the 16th century began it became even harder. Already stricken by famine and sickness, the population were subjected to extra taxation by the Fajardos, who by now were the Marquises de los Vélez and the military governors of the region, in order to finance protection against the Berber pirate attacks which were taking place along the coastline. In 1547, one of the townsmen, Pascual Rubio, at last took legal action against Luís Fajardo, the Marquis at the time, and although the dispute lasted over 40 years, until 1592 - the Spanish legal system was not famed for its speed even then! - it was eventually decided in favour of the common people. While the Marquis claimed that rights had been granted to his predecessors for "time immemorial", the court found that in 13 of the 16 points challenged, they had not.

However, the 3 points in which the Marquis’ claims were upheld were the worst for the townspeople: they still had to hand over a quarter of their crops obtained by irrigation, an eighth of all those achieved on non-irrigated land, and a 12th part of their crops of barilla (a plant from which soda was obtained).

During the 16th century the population rose from 432 in 1530 to over 1,000 in 1587, reaching 1,200 by 1620. However the instability of Alhama left it susceptible to further decline, and in the next 25 years the figure dropped to 400 before being further slashed to only 160 by what became known as the Great Plague of Sevilla in 1647-48.

At this point in history the livelihoods of those living in Alhama depended almost entirely on agriculture, with different activities taking precedence depending on the time of year. In March the vines required care and mulberry trees came into leaf, from April to June those mulberry leaves were crucial for the cultivation of silkworms and barley needed to be harvested, more cereals required harvesting in the summer and in autumn the fairs of September and October coincided with the grape and olive harvests and the start of activity to transport ice from the snow wells in Sierra Espuña to Murcia and Cartagena.

Of course, much of this agricultural activity was dependent on rainfall, and in the early- to mid-16th century a 7-year drought led to a decrease in the population, but by the end of the century silk production in Alhama and other parts of Murcia was higher than ever.

The Spanish War of Succession and the 18th century

In the early 18th century Alhama took the side of the Borbón dynasty in the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714), and helped to defend the city of Cartagena against the English and Dutch threat. Once peace was restored, the Region of Murcia flourished, and the baroque building boom which provided Murcia Cathedral with its façade also spread to Alhama: buildings dating from this time include the Iglesia de la Concepción, parts of the Iglesia de San Lázaro Obispo, the Casa de la Tercia and the municipal "pósito" (or grain store).

The early 19th century: fighting the French and the feudal lords

The War of Independence, also known as the Peninsular War (1808-1814), had far-reaching effects on Alhama, although in numerical terms more casualties were due to famine and yellow fever than to the fighting.

The location of the town, on the main route from Murcia to Andalucía, on flat, open land and without fortified defences, made it vulnerable to attack, while the castle was in ruins and had been abandoned since the 17th century. Three of the town’s Mayors, José Solana, Benito Aledo and Juan Vidal, supported the Junta de Murcia by contributing provisions, horses and money, and offered similar help to the guerrilla forces which were organized as a kind of civil militia, fighting Napoleon’s troops in small ambushes and skirmishes and using the element of surprise as one of the key elements of its weaponry.

Despite this, though, Alhama was attacked various times. For example, in 1810 the French scattered local resistance before attacking and destroying the grain deposit and setting fire to a range of buildings in the town, including the Ayuntamiento and part of the Municipal Archive.

During the hostilities the town council requested that Alhama once again become dependent directly on the Crown, and this request was finally granted in 1809. In this way, just two years before the formation of the Cortes of Cádiz Cortes (the first national assembly to claim sovereignty in Spain, to abolish the old kingdoms and to move towards liberalism and democracy), Alhama finally threw off the feudal yoke and freed itself from the rule of the Marqueses de los Vélez.

During the reign of Fernando VII, which lasted until 1833, the process of recovery was slow, and to some degree the overlords reasserted their power in Alhama, with Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, the 13th Marqués de los Vélez, being the last "Lord of Alhama" until 1834. This was the year when Alhama finally returned to being directly dependent on the crown once and for all.

The 19th century, a period of growth

The reign of Isabel II (1833-68) marked a definite upturn in the fortunes of Alhama, due mainly to an increase in the productivity of crop farming. Now that there were no longer any intrigues among the ruling overlords to hamper progress, an air of prosperity soon abounded in the town, and much of the architecture in the Plaza Vieja, Calle Larga and Calle Corredera dates from this period. One important innovation was the inauguration of the new Casas Consistoriales (or Town Hall building) in the Plaza Vieja, with far more modern facilities, including "a spacious, well ventilated and comfortable prison".

The freeing of ecclesiastical property from encumbrances, which revolutionized land in many rural areas of Spain, had little effect on Alhama, where the parish of San Lázaro owned no land and the Franciscan hospice was maintained by charitable donations. More important locally was the freeing up of land which occurred thanks to the reforms promoted by Pascual Madoz in 1855, which effectively harmed the lower classes by taking away from them pasture land, water, esparto grass, coal, firewood and even arable plots.

Even now, the main pillar of the local economy was agriculture, the principal products continuing to be grapes, wheat, barley and olive oil, a large proportion of all of them being exported to as far away as Madrid, Paris and even London. At the same time oranges were making their first appearance in the rural landscape, while figs and prickly pears were also cultivated.

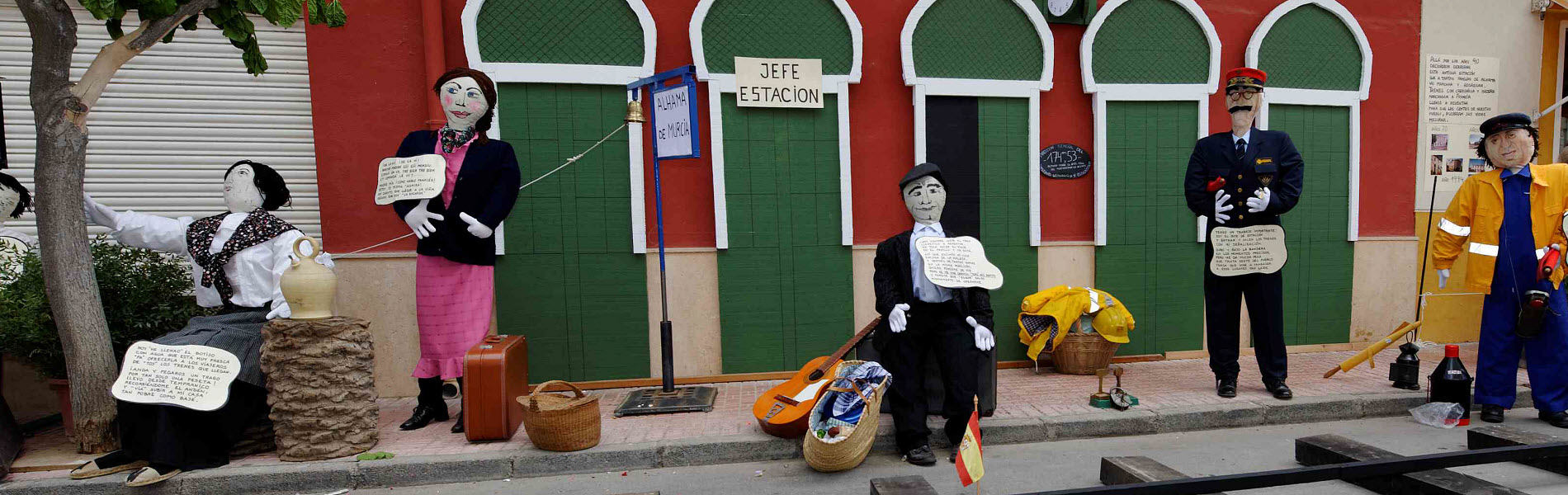

Outside agriculture there was also a significant amount of vegetable coal production, and a few mineral mines which were under-exploited due to the difficulties of transporting the metals to factories and ports: this lack of transportation was at least partially remedied by the completion of the Murcia-Águilas railway, passing through Alhama, in 1885.

Naturally enough, economic growth brought with it population growth, and census figures show a steady rise from 1,244 in 1717 to 4,028 in 1800 and 7,203 in 1887. This was despite the effects of outbreaks of typhus, smallpox and cholera, the last of which killed 314 residents of Alhama in 1885. At the same time, an agricultural crisis had led many people to re-locate either in Murcia or in the reactivated mining areas of Mazarrón, La Unión and Cartagena, while others went further afield, to Orán (in Algeria), Catalunya or South America, and as a result the population had dropped again to 5,122 by 1891: two thirds of these (3,320) lived in the town itself and the remainder in the surrounding countryside.

So, the growth of the town was all but halted, although a positive side-effect of the emigration was that a balance was achieved between supply and demand in terms of basic foodstuffs and labour, avoiding famine, unemployment and social conflict.

In 1848 a large spa and hotel complex was built, consisting principally of a 3-floor building on the site of the Roman remains. The basement comprised the bath-rooms, showers, steam baths and the public pool which was for the use of the poor people of the town, and above this was a luxury hotel, standing on the site which is now occupied by the “Los Baños” archaeological museum.

By1877 the number of people visiting the baths of Alhama had reached 1,000 a year, and this influx of visitors and the rising population were two of the factors which led to public street lighting being installed in 1858. Ten years later these were altered to use mineral oil, then in 1882 petroleum was used in all 34 lamps, the number increasing to 51 in 1892.

Finally, in 1904, the company “Eléctrica Alhameña” was founded and installed 50 electric lamps in the streets three years later.

It was also in the late 19th century, in 1895, that the annual fiestas were instituted to coincide with the feast day of Nuestra Señora del Rosario.

The 20th century: Alhama moves into modern times

As new infrastructures were created, so the land in and around Alhama became more valuable. Particularly important in this development were the main road and the railway between Murcia and Granada, with branches leading to Alicante, Cartagena and Águilas.

Another highly significant development came in 1914, when the slope of the mountain beneath the castle was dug out to build a large drinking water deposit, ensuring that the population had an emergency water supply. The water was known as the locally as the "Aguas del Caño", and any surplus water in it was used to supply the Fuente del Caño.

In 1919, two more drinking fountains were built, one of them in the Jardín de los Patos, and for many years this was the only drinking water supply in the town apart from the freshwater springs of the Sierra Espuña, but they were enough to allow the population of Alhama to grow from 8,000 at the start of the 20th century to 11,000 by the end of the Civil War in 1939.

In addition, with the thermal spa continuing to attract visitors from all over Spain, the electrification of street lighting continued, and by 1917 the number of lamps had risen to 150. In the meantime, the name of the town had been officially changed to Alhama de Murcia in 1916.

This expansion coincided with the building of the Casa de los Saavedra (home to the Centro Cultural V Centenario), the current Ayuntamiento (Town Hall), which was inaugurated on 22nd May 1923, and the Plaza de Abastos food market (1928), but during the Civil War the spa hotel was converted into a hospital and the spring waters practically disappeared. The building was demolished shortly afterwards.

In 1952 water from the Taibilla reservoir began to reach Alhama, and more public water taps were installed along with the sewage network, a water purification plant, the waste water deposit and the public washhouse. In addition, more water was now available for irrigation, although table grapes continued to be the most common agricultural product.

Under the régime of General Franco (1939-75) the town’s population stagnated, but since 1970 it has almost doubled to over 21,000, and the expansion of the built-up area has led to the construction of new public parks, squares and buildings, including the Plaza de la Constitución, the Parque de la Cubana and the Jardín de los Patos. These are now the hub of Alhama’s social and economic life, while the old Plaza Vieja, with its imposing noble houses and the Fuente del Caño, has become secondary in importance.

Alhama in the early 21st century

Among the population of over 20,000 approximately 20% are non-Spaniards, mainly of Moroccan, Bolivian and Ecuadorian origin and working in agriculture. This says a lot about the way in which Alhama de Murcia grew in the 20th century, with the possibility of irrigation at last ensuring that the most was made of the fertile soil in the Guadalentín valley.

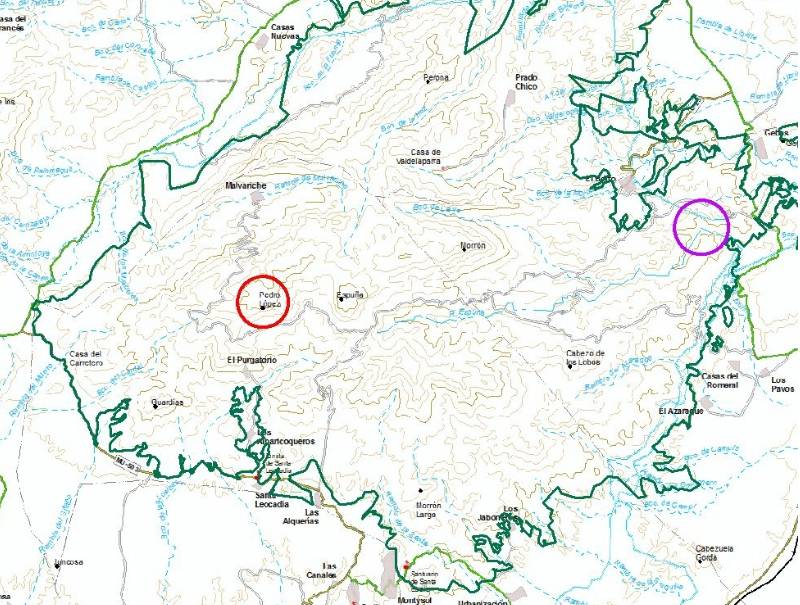

The plain is full of crops, 6,508 hectares of which are irrigated (due in large part to the Tajo-Segura water supply canal, which came into service in 1977), and the traditional table grape is now grown alongside citrus fruit, peppers and other fruits and vegetables. A further 9,478 hectares are devoted to non-irrigated crops.

Also belonging to the food sector is the largest single employer in the town – and indeed one of the largest in the private sector in the Region of Murcia. This is El Pozo, belonging to Grupo Fuertes, whose meat products are well known sold all over Spain as well as being exported throughout the world, and whose main factory is unmissable from the motorway which now links Alhama to the rest of Murcia and southern Spain. El Pozo started as a small processed meat shop in Alhama in 1936, and with annual turnover of around a billion euros is now the second largest company in Murcia. Together with a shoe-making tradition which began in the 1940s, the sector has contributed to Alhama gradually becoming less dependent on its agricultural activity for economic prosperity.

As well as the Moroccans and South Americans, though, there are also almost 1,000 from the rest of the EU, including over 250 from the UK, and this is due largely to the construction of the largest of the Polaris golf resorts within the municipality. Many of the buyers at Condado de Alhama are British, and they live in a municipality which is alive to the possibilities afforded by tourism at the start of the new millennium: while the town is within easy striking distance of the Bay of Mazarrón, the beaches of the Costa Cálida and the Region of Murcia International Airport in Corvera, it is also at the foot of the Sierra Espuña, where the Regional Park is often referred to as the "green lung" of the Region of Murcia.

The highest peaks are over 1,500 metres above sea level - that's higher than Ben Nevis! - and a total of 18,000 hectares of protected land lie in the municipalities of Alhama, Totana, Mula, Aledo and Pliego. Most of this is covered in pine forest, thanks to the re-planting undertaken by the engineer Ricardo Cordoniú at the end of the 19th century, and among the most interesting features are the snow wells, or ice-stores, on the uppermost northern slopes.

In other words, after centuries of suffering and hardship due to the problems inherent in a geographical location which was for a long time considered “frontier territory”, Alhama is now making the most of a combination of its mountain scenery, its proximity to the coast and its position on one of the major communications routes of south-eastern Spain to forge a prosperous future.

For more local information, including news and forthcoming events in English, visit the home page of Alhama Today.

Welcome To

Welcome To Alhama de Murcia

Alhama de Murcia

Welcome To

Welcome To Alhama de Murcia

Alhama de Murcia

Welcome To

Welcome To Alhama de Murcia

Alhama de Murcia

Welcome To

Welcome To Alhama de Murcia

Alhama de Murcia